The Abridged version:

- Sacramento State gerontology students pair with mentors from the Renaissance Society, a campus program geared toward older adults, to further their learning about aging.

- The generations share a distinction, according to national studies: Young and old adults are America’s two most isolated populations.

- One mentor said students he has mentored “acknowledged their perception of the elderly was very different at the end of the class than from the beginning.”

Two of America’s most isolated populations are coming together in the name of emotional well-being.

At Sacramento State University, students in the gerontology department are learning about loneliness. But the youngers may be just as isolated as the olders they are studying.

“Ageism is so prevalent that not a lot of people know that gerontology is a field that you can study, or even what gerontologists do,” said Donna Jensen, professor emeritus and former chair of the department. “A big piece of my job is to educate students, potential students and people in the field what gerontology is. It’s a study of aging.”

Students in the department fall into three categories: Some are care providers who are formalizing their education. Others are headed for positions in government agencies that provide services related to aging. A third group enters the field without a clear career goal in mind.

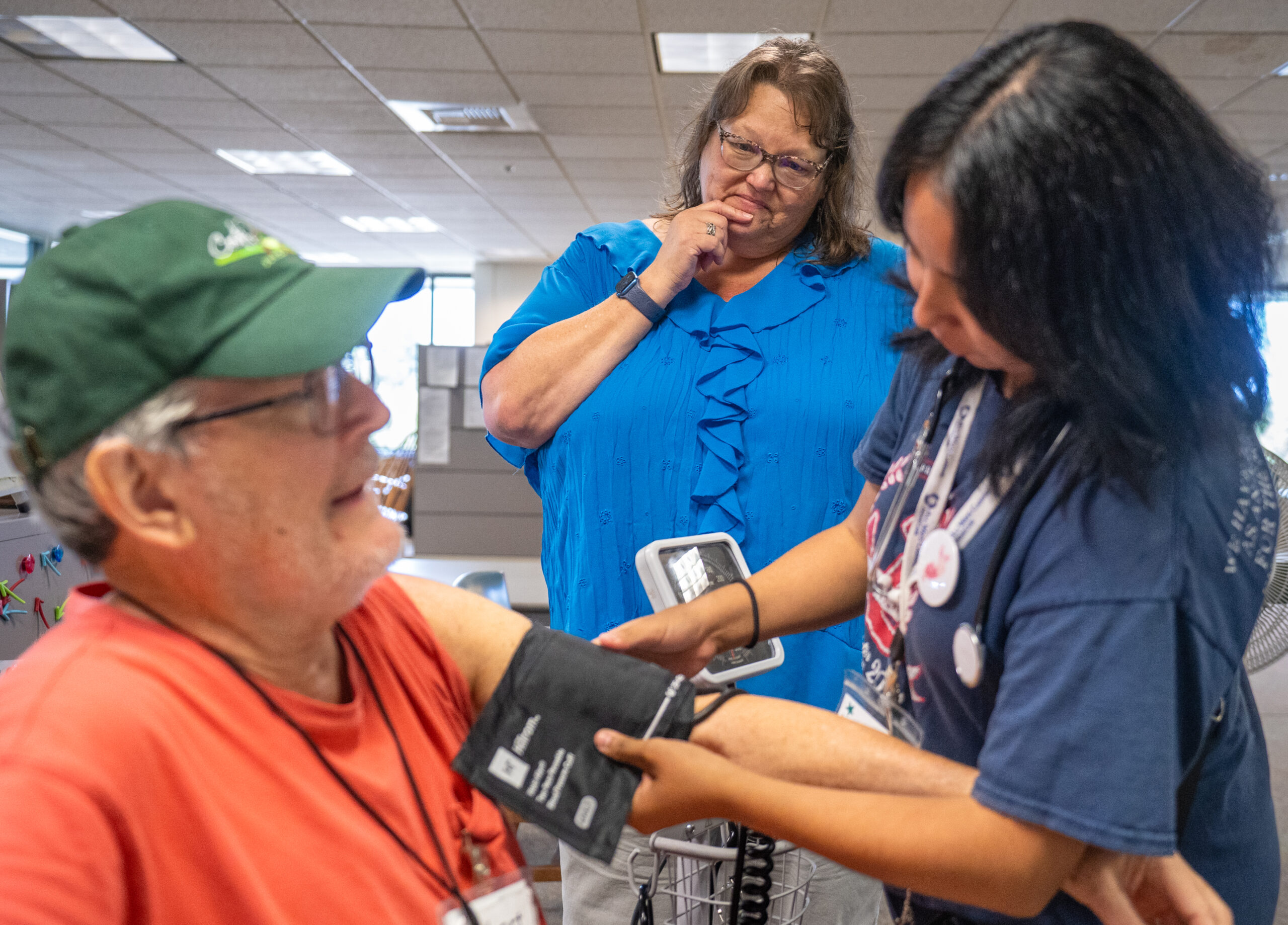

The department’s Strategies for Optimal Aging course has a built-in mentoring program that gives students a unique opportunity to build a relationship with someone from their grandparents’ generation. Every student in the semester-long course is paired with a person over the age of 55.

Students and mentors share a degree of loneliness

Gerontology students and the adults they study may share a degree of loneliness. According to a 2023 report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, America’s two most isolated populations are young adults and older adults. Those in college are almost twice as likely to report feeling lonely than those over 65.

“We know, maybe, what it feels like,” Jensen said. “We know what it might look like, but it’s kind of difficult to define.”

While isolation has to do with who is around us, loneliness is a lack of connection.

“You could be lonely in a room full of people,” Jensen said. “I’m surrounded by family, but the only time I see them is when the Wi-Fi goes out, and they come out and say, ‘What’s going on?’ We’re missing that connection.”

Mentors are members of the Renaissance Society at Sacramento State

Isolation and loneliness come up in conversation between students and their older mentors. The olders are members of Sacramento State’s Renaissance Society, an extensive program of classes and social opportunities geared toward older Sacramentans. Mentors and students sign a one-semester contract and agree they will not reveal each other’s identity, visit each other’s home or drive together.

“It is so beautiful,” Jensen said. “You get to see students changing their view on aging. Not only helping them look at aging differently, fight some ageism, but many of them are connected with their mentors long after the class is over.

“The students and the mentors just feel like it’s a gold nugget for them.”

“I see students giving advice to mentors, and mentors giving advice to students.”

Jenny Stevenson, instructor of the Strategies for Optimal Aging class

Jenny Stevenson, who teaches the Strategies for Optimal Aging class, connected with a volunteer mentor 10 years ago when she was a student in the program. She said the mentorship sometimes becomes a friendship that extends beyond the semester.

“A lot of them still talk to their students to this day,” she said. “I know I still talk to my mentor from 2014.”

“The mentorship component is basically the core backbone of the whole course,” she explained.

Social relationships, health and spirituality on the agenda

Early in the semester, students write a paper that explores their own values and perspectives based on a set of criteria. Then they meet with a mentor (three or four meetings lasting approximately 45 minutes) to ascertain that person’s values and perspectives.

Some of the key elements for discussion include social relationships – how to form them and how to mend them – physical health, mental health and spirituality.

“Spirituality doesn’t mean that necessarily either side is religious,” Stevenson said, “but they talk about these different outlets in life when stressful times come about, and their spirituality making them feel safe, and it’s OK, and everything’s gonna work out.

“That can work both ways. I see students giving advice to mentors, and mentors giving advice to students.”

Although enrollment varies from year to year, fall semester 2025 saw approximately 90 student/mentor pairs.

Many students have not been exposed to grandparents or other seniors

Rob, 77, has mentored five students over the last eight years. In keeping with the mentoring program’s contract, we are not using the names of the students he mentors. Abridged agreed to use only his first name because of the anonymity requirement in the student-mentor contract.

In his experience, students haven’t been exposed to olders.

“In our current society, many 20-ish students either don’t have grandparents or have no interaction with the ones they do have,” Rob said. “Each one of my students acknowledged their perception of the elderly was very different at the end of the class than from the beginning.”

Conversations between Rob and his mentees are respectful and discreet.

“Both the student and I reserved the right to politely decline any discussion that felt awkward or uncomfortable,” he said. “To make them feel more at ease, I would occasionally ask them questions about their lives. They loved to share their experiences and tell their stories. And I love to hear them.”

The collateral benefit for Rob is evident. “In one word, ‘amazement,’” he said. “They are so smart, so perceptive and interesting to be around. It’s so inspirational and refreshing to be around today’s youth and learn what they think.”

Jensen said specific traits mark a difference between olders and youngers.

Resilience a key difference between mentor and student

“I tie it a lot to resilience,” Jensen said. “And what I’m most worried about with generations coming up is the lack of resilience – the need for immediacy. The ‘I can’t wait. I have no patience.’ You build resilience by going through some painful times, having to figure it out.

“But I also worry about what we’re missing and the ability to engage, which is where empathy comes from – caring about people, the ability to deal with people. I worry that future generations may not have that because the hardships aren’t the same. In the long term, our resilience and our hardiness are key components of aging optimally.”

She explained that the gerontology department has other solutions built in.

“If you hit an older with, ‘I think you’re lonely,’ what’s going to happen? ‘Oh, no, no, I’m not lonely,’ because we affiliate that with some kind of interpersonal issue and not a societal issue. And so students will work on, ‘What do you want to do? What do you want your life to look like?’ as much as possible. That is really helpful for both populations.”

With many friends and close family, Rob does not feel isolated, but he has discussed the topic with his mentees.

“I did experience one female mentee who recently emigrated from (another country), and loneliness and isolation were a big part of her life.”

Isolation can build for olders; a warning for younger groups

Jensen pointed out the snowball effect of isolation for today’s older population and as a warning to younger groups.

“The more you isolate, the harder it is to get through and reach out,” she said. “The more you get into that situation, it becomes so much more difficult to learn that skill, and socialization is a skill.”

She posed two key questions that apply to all age groups:

“Why, as a society, are we OK with just letting people be lonely and isolated and alone and disconnected?

“And what are we each doing to intentionally reach out to people?”

Donna Apidone is a regular contributor, writing Coming of Age for Abridged.