The Abridged version:

- Sacramento artist Peter VandenBerge’s art has been displayed in places like the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Louvre in Paris.

- At the age of 7, VandenBerge was separated from his family and forced into a prisoner of war camp in Indonesia.

- VandenBerge gained fame as part of the “Funk Art” movement in Northern California. He opens up about how his POW experience influences his art.

At 90, artist Peter VandenBerge is opening up about the deeply personal story that inspired his world-renowned art. VandenBerge creates his highly collected clay creations in his Sierra Oaks studio with the same gentleness by which he lives.

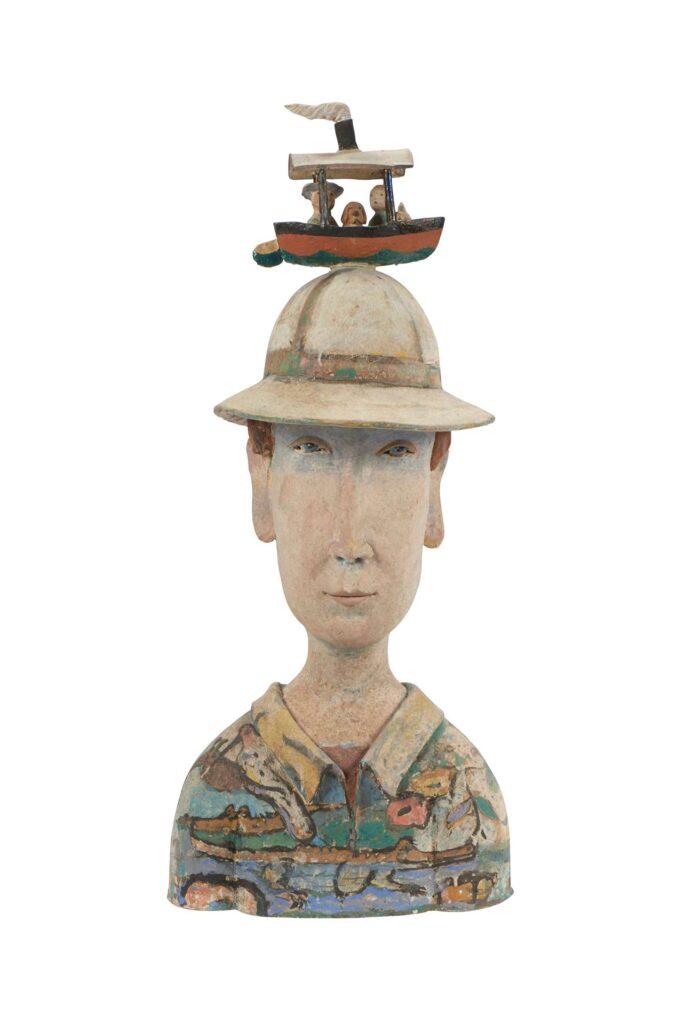

His ceramic busts — with signature elongated faces — tell a story, many times with an object on top, such as a boat, car or teapot. Each one is an echo of something he’s lived, survived or overcome.

For the first time, he shared his story in-depth, detailing how he survived unimaginable circumstances as a former prisoner of war.

“I have so much gratitude and really, I have peace,” VandenBerge said.

A childhood interrupted by war

VandenBerge was born in The Hague in the Netherlands in 1935. His father, a geologist with Royal Dutch Shell Oil Company, moved the family to Indonesia, then the Dutch East Indies. VandenBerge vividly recounts scouring mountains and caves with his dad on the islands of Java and Sumatra. It was a magical time for VandenBerge, exploring rivers and the red clay earth.

“I would go with him on his back, you know? Up and down volcanos, you could see smoke coming out,” VandenBerge said. “Maybe that’s why I got involved in clay.”

It was an idyllic childhood until 1942. The Japanese invaded Indonesia, and the VandenBerge family was thrust into the chaos of World War II.

“They wanted to conquer the whole Pacific,” VandenBerge said. “We were caught up in it.”

One night, VandenBerge, his parents and 2-year-old little brother, tried to flee.

“We had an old Chevy,” he said. “My father told us to put these little rubber pieces in our mouths so the bombs wouldn’t break our teeth.”

As they drove through rice fields — their headlights darkened by blue pieces of paper —Japanese planes opened fire from above. His father shouted for everyone to jump out of the car and hide beneath a bamboo house — but got trapped.

“There was no escape,” VandenBerge said. “So, my mother was out and took the baby, and I’d say maybe about a couple of minutes after we did that, that Japanese airplane came and started shooting. And I remember as, as if it happened yesterday, the bullets. The bullets coming toward us hitting the sand. That’s just one of the things that happened to us. But the whole family made it, which is amazing.”

Days later, the family was captured by the Japanese Imperial Army. His father was taken to a men’s camp, his mother and brother to another camp, and 7-year-old VandenBerge — sick with whooping cough — was left behind in a village.

“A doctor and her family took care of me for three months,” he recalls. “But one day, the Japanese came back. They remembered me.”

Life as a prisoner of war

For three years, VandenBerge lived inside a series of POW camps in Indonesia. Life was starvation, exhaustion and fear. The prisoners were counted three times a day under the tropical sun. Anyone who broke the rules was brutally punished publicly.

“If someone tried to sneak food, we were forced to watch what happened,” VandenBerge said. “I still see it when I close my eyes. There were two women, they tried to get food, and they buried them up to their neck in the ground. They beat them with whips and all kinds of things. They made us watch what they were doing and said the same thing would happen to you. I saw them poking their eyes out, I know I saw that because I remember looking through legs, you know I was a little and I saw them, and to this day, I still remember that which is like beyond belief.”

The women were left to die, VandenBerge said.

At night, a sound haunted the prisoners in the camp.

“They put the dead on a cart with metal wheels,” VandenBerge recalled. “You could hear it rolling over the bricks in the dark. Everyone knew what it meant — someone had died.”

VandenBerge paused, tearing up. “Even the children lost their spark. The hopelessness was everywhere,” he said.

Amid the cruelty, one small act of humanity shaped the rest of VandenBerge’s life.

“There was a Japanese soldier,” VandenBerge said. “He watched over the children. We asked him, could you maybe get us paper and pencils? I didn’t expect anything. But he did.”

Those pencils and scraps of paper became a lifeline. In the midst of war, young VandenBerge drew.

“That’s where I really got things,” he said. “That’s where it began.” It was the first time he used art to survive — and the beginning of a lifelong language of resilience.

From captivity to creation

After Japan’s surrender in 1945, VandenBerge’s family reunited and fled to Australia. Eventually, he returned to Holland before immigrating to the United States. At just 19, he boarded a small cargo ship from Rotterdam to New York, working his way across the Atlantic.

Somewhere between Europe and America, a hurricane hit.

“The boat was rolling side to side,” he recalled. “It was terrifying. But I made it.” That terrifying journey is reflected in his art depicting a boat on top of a bust.

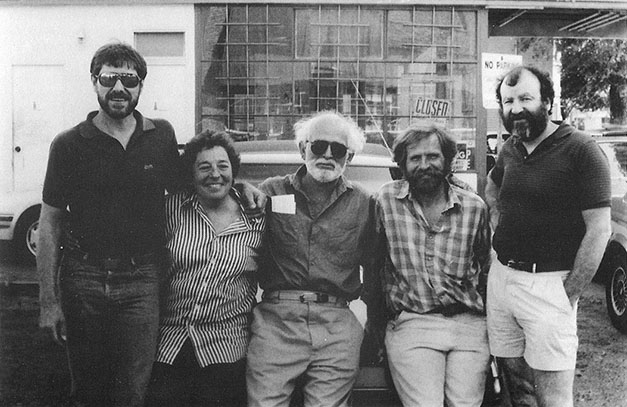

VandenBerge settled in California, graduated from Sacramento State in 1959 and began studying for his master’s degree. In 1961, VandenBerge saw Robert Arneson doing a clay demonstration at the California State Fair. Impressed by what he saw — and with an offer for part-time work alongside Arneson, VandenBerge transferred to UC Davis, completing his master’s degree in 1963.

He stayed at UC Davis and kept his hands in the clay, working at the foundry at TB9, which became a central hub for influential artists of the era. That’s where he helped to develop a new type of whiteware clay that he, Arneson, and others would use in making the ceramics that gained famed as part of the “Funk art” movement.

“It was wonderful,” VandenBerge said. “Thought-provoking and alive. We were building something new.”

His contemporaries included Wayne Thiebaud, Ruth Rippon and William Wiley. Together, they forged a bold, humorous, and human aesthetic that redefined West Coast art.

Gaining fame, and visiting Japan

For nearly seven decades, VandenBerge’s career has flourished. His exhibits have included San Francisco’s MOMA, Whitney Museum in New York and the Louvre in Paris. His permanent collections are in the Crocker Art Museum and the Smithsonian American Art Museum, which houses one of his most famed sculptures, Madame Matisse.

In 2006, VandenBerge’s story came full circle. He and his daughter, Camille VandenBerge, herself a gifted artist, were invited to Shigaraki Ceramic Cultural Park in Japan.

“I told them my story,” he said. “About the soldier who gave us paper and pencils. About how art saved me.”

Standing on Japanese soil, he felt no anger — only gratitude.

“I felt peace,” he said. “A quiet peace that I don’t have to go through all that anymore.”

A life forged in clay

Today, at 90 years old, VandenBerge still works daily in his studio, often side by side with Camille. Together they create monumental figures that stretch upward, faces calm, eyes alert. Every surface tells a story – not of suffering, but of survival.

“Don’t take things too seriously,” he says. “Enjoy what you can. Make life an enjoyable experience.”

After all he has endured, those words carry more weight than most could imagine.

“People who survived,” VandenBerge said, “were the ones who could still see something good. Who helped each other. Who found joy.”

Rob Stewart is an executive producer and reporter for Abridged.

Related by PBS KVIE: Peter VandenBerge’s story