The Abridged version:

- Health clinics affiliated with houses of worship in Sacramento and Roseville provide free care to people who lack insurance and English language skills.

- Some of the patients also are undocumented, which has led to heightened fear as federal immigration enforcement efforts ramp up.

- The clinics are staffed by volunteers, including medical students and doctors from UC Davis.

In an obscure waiting hall in Midtown Sacramento, Virk couldn’t stop running his tongue over his newly cleaned teeth. The 20-year-old undocumented immigrant, wrapped in a black turban, has never had dental insurance and has never been able to afford the cost of American dental care.

But on this November Sunday, he received his first cleaning, free of charge, at Shifa Community Clinic.

“In the United States, dental care is exorbitant,” Virk said in his native language, Punjabi. “The free clinics like Shifa are doing a great service to the community.”

Outside the clinic, as fallen leaves littered V Street in Downtown Sacramento, prayers echoed from the nearby mosque. At 10 a.m. on Sunday, parents dropped off their children for services. Next door, undergraduate students, most whom aspire to medical careers, arranged clipboards and sanitized equipment. Medical students reviewed patient charts between bites of doughnuts and sips of coffee.

Dr. Shagufta Yasmeen pushed through the Shifa community clinic’s door, ready to begin another day of volunteer service.

For 23 years, Yasmeen has spent Sundays at the clinic, which started as a single exam room in 1994.

“It was created with an aim and an opportunity for the undergraduates as well as the medical students to interact with the community and to provide free care to patients who do not have access to care,” Yasmeen said.

Free clinics are lifelines to immigrants

The Shifa Clinic and others such as the 5 Rivers Heart Association, which operates a weekly free clinic at a Sikh temple in Roseville, have become lifelines for Sacramento’s uninsured and insured immigrants — a place where language is never a barrier and care comes without questions about immigration status.

The percentage of uninsured Californians reached record lows in 2024, but nearly 2.57 million people remained uninsured, including 520,000 who were undocumented and ineligible for insurance, according to a study by UC Berkeley’s Labor Center.

Immigration enforcement brings layer of fear

For many immigrants, the challenge extends beyond insurance — it is about finding doctors who speak their language, understand their culture and are willing to provide care even with the threat of immigration enforcement. The doctors said that the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement crackdowns have created an atmosphere of uncertainty with undocumented and uninsured people, many of whom are avoiding hospitals for fear of detention.

“There is a great fear,” said Dr. Swaiman Singh, an assistant professor at UC Davis who founded 5 Rivers Heart Association. “I had a patient whose wife just got pregnant. He was undocumented, and they were afraid to go to the hospital. So I had to persuade them to go to the hospital. So it is a huge thing that we’re seeing right now in the community — the fear.”

At the same time, medical students volunteering at the free clinics worry that recent federal legislation will strip millions more from health coverage, expanding a health care access crisis.

ICE says it will not ‘indiscriminately’ enforce at clinics

In a prepared statement, ICE said the agency is not obligated to avoid places some consider immigrant sanctuaries as it carries out immigration enforcement.

“While ICE is not subject to previous restrictions on immigration operations at sensitive locations, to include schools, churches and courthouses, ICE does not indiscriminately take enforcement actions at these locations,” the statement said.

Culture of comfort

Inside Shifa’s exam room that Sunday morning, Maite Garcia, a second-year UC Davis medical student, was examining a 46-year-old Brazilian patient, Jacqueline, experiencing symptoms of perimenopause.

For Jacqueline, having access to care in her native language made a significant difference. The clinic had provided a college student fluent in Portuguese to serve as a translator.

“It’s very detailed appointments, so I feel very welcome here,” Jacqueline said. “Because there are students, too. They actually want to know what’s going on. They take their time, and they care,” she said through the translator.

Garcia completed the examination and discussed the case with Dr. Yasmeen, who then gave a consultation with Jacqueline.

Language barriers dissolve for many immigrants

The language barrier that intimidates many immigrants at traditional hospitals dissolves here. The clinic provides translators for Spanish, Portuguese, Middle Eastern and South Asian languages.

According to Yasmeen, 40% of the clinic’s patients are Hispanic, followed by the South Asian and Middle Eastern populations. A significant Portuguese community also seeks care there.

“If somebody comes from India, I am able to speak to them in my own language, and they feel like home, and the same thing with the Spanish or Portuguese people,” Yasmeen said.

Care includes weekly appointments and monthly women’s health camp

Each Sunday, the clinic serves up to 14 patients who have booked appointments and also holds women’s health camps every second Saturday. Nearly 10 physicians volunteer on a rotating basis.

“It’s tough to get the physicians to volunteer because of Sunday, as they are busy, but we have faculty from UC Davis, who have been coming to the clinic for the last 25 years now,” Yasmeen said.

Dr. Mohammad Khan, a UC Davis cardiology fellow, started the Shifa clinic in 1994 at the mosque’s request, recognizing that people who came from abroad didn’t have access to health care. It was a tiny clinic — one room with one table, one stethoscope, and a chair.

The operation has expanded dramatically. Three years ago, Shifa added a dental clinic to address a critical gap. Nearly 5.2 million Californians lacked dental insurance, according to a 2019 American Dental Association report.

The clinic operates independently of the mosque but maintains ties. It pays rent for two apartments while receiving two others for free. Most of the equipment has been donated.

“We raised funds from the community,” Yasmeen said. “We do fundraising every year where the community comes together … , almost about $100,000 to $150,000.”

UC Davis provides additional support, offering all lab tests at no cost to patients, alongside $20,000 to $30,000 annually, Yasmeen said.

Personal mission

Shifa is family for Garcia, who is fluent in Spanish.

The experience, she said, has allowed her to continue to grow. “I definitely wanted to challenge myself a bit more.”

A personal connection drives her volunteer service. Her father lacked health care and traveled to Tijuana, Mexico, to receive treatment.

“I went into medicine because my father himself didn’t have health care, and … it really felt very personal to volunteer for the clinic,” she said. “Just know it has been so rewarding.”

Faith and healing

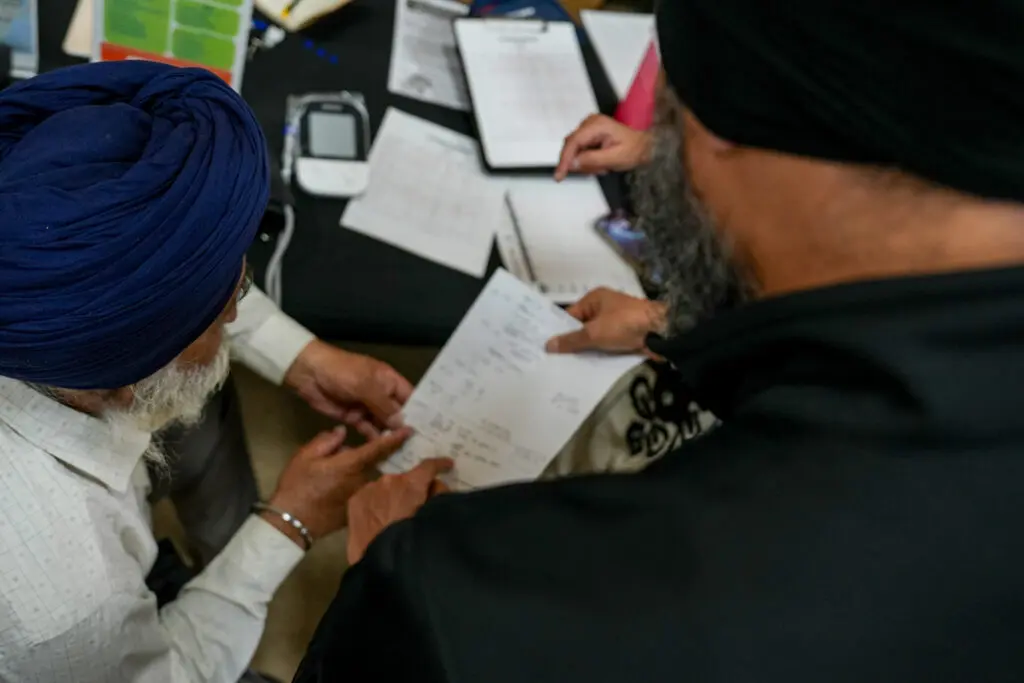

In Roseville, 22 miles from Shifa Clinic, Singh and his team hold their weekly Sunday free clinic at a Sikh Temple. On a recent Sunday, hundreds of Sikh devotees were paying their obeisance in the temple and sharing a community lunch in the temple.

Singh’s team was taking notes on the medical histories of that day’s patients while his colleagues were consulting with them.

Kuldip Singh Brar, a 70-year-old heart patient, discovered the clinic through Facebook. He said he was inspired by Singh’s approach.

“I shared my entire medical history with Dr. Singh, and he alerted me to some important concerns and prescribed new medication,” Brar said. “Singh prescribed me two new medicines which may help increase my life expectancy. … Other doctors have never inquired in such detail or asked such thoughtful questions about my condition.”

Rajinder Singh Mann, 71, stopped by the clinic while visiting the temple. He wanted to check his blood sugar levels to see if his diabetes had worsened. “I wanted to ensure that it stays still within limits,” he said.

The ability to communicate in Punjabi makes all the difference. “The doctors are doing a very good job educating the community. But the main thing is that patients can speak in Punjabi. It’s much easier for people to describe their problems in their own language,” Mann said.

Singh’s clinic offers to check blood pressure, diabetes screenings and blood work. If the patients need any radiological scans, the organization pays for them. If they have insurance, the clinic team reports to the patient’s regular doctors.

Roseville clinic sees 100 to 150 patients each week

The 5 Rivers Heart Association mobilizes a team of about 65 doctors in Sacramento who volunteer on weekends, depending on their availability. They see 100 to 150 patients weekly.

For Singh, the work is deeply personal. His maternal grandmother didn’t receive adequate care in India and ended up with chronic kidney disease, which could have been easily prevented. His paternal grandmother died in California after failing to get the care she needed. She lacked health coverage.

The team holds free clinics at Sikh and Hindu temples, mosques and churches throughout the city. Team members leave some of the equipment wherever they go, so it’s easy to set up the clinic every week. Nearly a dozen doctors, including Singh, spend about $100,000 annually on free clinics, he said.

His goal is simple: Everybody should have the same level of health care.

“Whatever the patients need,” he said, “whether it comes out of our pocket, as an organization, or it comes out through the insurance they have at the end of the day,” Singh said.

“I feel like pain is something that we need to wipe out,” he said. “Suffering leads to suffering of families, communities. So I think as a doctor it’s my commitment to my field that if somebody is in pain, that I should be there to help them.”

Gagandeep Singh is an independent journalist based in Sacramento.

Abridged visual journalist Denis Akbari produced a video inside the free health clinics.