The Abridged version:

- A local author describes her family’s experience of being removed from their Sacramento home and placed in an internment camp in 1942.

- Kiyo Sato is 102, and is still an active speaker, advocate and organizer.

- “I feel terribly,” Sato said about present-day immigration enforcement. “We are repeating history again. I have friends in fear. I know that fear.”

Kiyo Sato does not speak about history as something distant.

She speaks about it as something that lives inside her.

At 102 years old, the Sacramento author has told her story to thousands of people. With each passing year, her message clearly lands with quiet yet growing force. Not because it is dramatic, but because it is precise. Because she remembers details others never learned. Because she watched ordinary life unravel, step by step.

Many of those memories still break her heart.

When soldiers came for her family in Sacramento during World War II, Sato was forced to leave her two dogs behind in the shed on her family’s property. “I left the shed door cracked open,” Sato said.

When the war ended and she returned home years later, the dogs were still there. They did not survive.

“The dogs had waited. They died of broken hearts,” Sato said.

For Sato, that loss has never been small. It is why, more than eight decades later, she continues to speak.

“I’ve seen this before,” she said.

A Sacramento life upended

Sato was born in 1923, the oldest child in a Japanese immigrant family in Sacramento. Her parents built a modest but successful fruit farm, raising nine U.S.-born children through hard work, cooperation and faith in the American dream.

By 1941, Sato was attending Sacramento City College, focused on her education and her future.

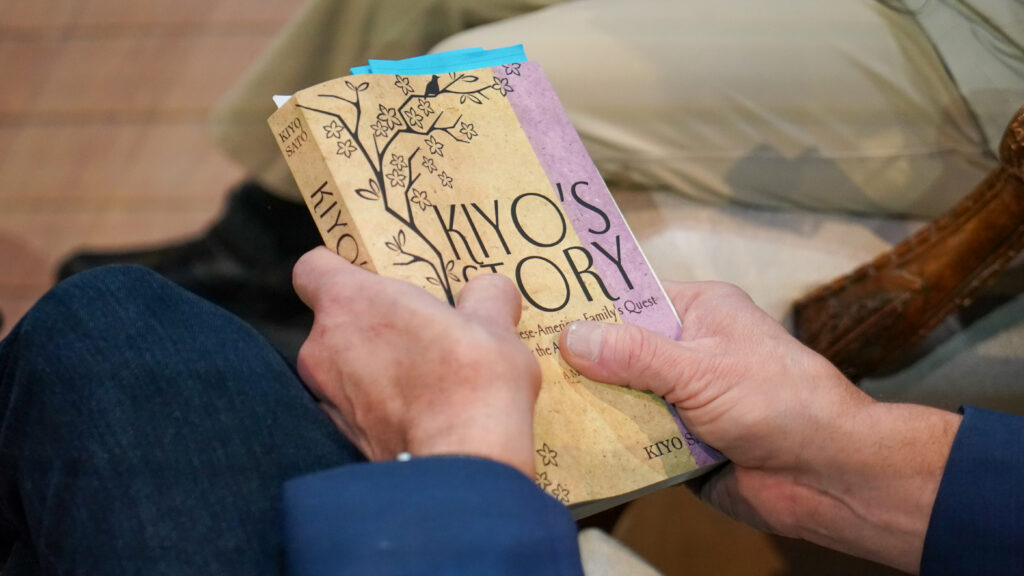

That future changed abruptly after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Five months later, she was followed by police near Folsom Boulevard and Bradshaw Road. In that moment, she thought to herself: “Dear God, please, please, not now!” according to her memoir, “Kiyo’s Story.”

Sign Up for the Morning Newsletter

The Abridged morning newsletter lands in your inbox every weekday morning with the latest news from the Sacramento region.

In May 1942, under Executive Order 9066, Sato and her family were forced from their home and sent to the Poston War Relocation Center in Arizona. Like thousands of other Japanese-Americans, they were removed not because of actions, but because of ancestry.

Sato was assigned an identification number. Her freedom was reduced to a tag.

“Number 25217-C,” Sato said quickly. “I have PTSD from that number.”

Inside the internment camp, she witnessed daily life shaped by confinement, surveillance and uncertainty. She has spoken openly about the long-term emotional toll of that experience, including trauma that never fully faded.

“It stays with you,” she said. “Your body remembers.”

The loss that still hurts

For her, the dogs she lost symbolize the unseen casualties of incarceration. Not just the land lost, the home ruined, or the years taken, but the living beings abandoned without explanation or mercy.

“They loved us,” she said.

On Monday at The Jacquelyn in Sacramento, Sato shared that memory with a packed book club gathered to hear excerpts from “Kiyo’s Story.”

Sato described the beds they slept on in the internment camps.

“They were made of straw and wrapped in plastic. It was 123 degrees outside,” Sato said.

The plastic was to be used, if needed, as a body bag. Some attendees wiped away tears. Others sat frozen, absorbing the weight of what had just been said.

It was not a history lesson. It was testimony.

A life of service after confinement

After the war, the Sato family worked as laborers in Colorado before returning to Sacramento to rebuild their lives. Sato chose a path defined by service, enrolling in the United States Air Force Nurse Corps. She eventually achieved the rank of captain before returning home to raise a family.

She is the mother of four children, all adopted. Today, she is the matriarch of five generations, more than 50 people spanning all races, beliefs and backgrounds.

“We look like the United Nations,” Sato said with a smile.

Service to her country, for her, was never incidental. It was a declaration that what had been done to her would not limit what she could give.

A daughter raised on advocacy

Cia Vancil, 66, the oldest of Sato’s four children, said advocacy was not something her mother taught intentionally. It was simply how she lived.

“She’s always been actively speaking for herself and for others,” Vancil said. “Everything she’s done in her life has been about service. Being a nurse. Being a veteran. Advocating for common folk.”

Adoption, Vancil said, was never hidden or complicated in their household.

“She told us from the beginning, you were specially picked,” she said. “As an adopted child, that changes everything.”

Discovering how little is taught about internment

Despite growing up with her mother’s story, Vancil said she was still shocked by how little the Japanese-American internment was covered in school.

“In my history book, it was two paragraphs,” she said.

At The Jacquelyn, audience members echoed that disbelief. Sato is used to the reaction. After reading Sato’s book, people have approached her with maps of Sacramento, asking where she had been followed by police in 1942. They wanted to drive the same routes. To stand where she stood.

“They wanted to feel it,” Vancil said, “because this happened right here.”

Advocacy at 102

Sato’s concern for others has not dimmed with age.

Vancil recently watched her mother write a letter to U.S. Rep. Ami Bera after witnessing a homeless man in crisis at a McDonald’s. Police were called, but the man was simply sent away, not connected to help.

“At 102, she was furious,” Vancil said. “She would not let it go. She was on her laptop writing about how we need to help people, not discard them.”

Every Sunday morning, Sato meets friends for coffee. Every Sunday night, Vancil brings groceries and cooks dinner with her mother. Even then, Sato is often writing, organizing or advocating.

“She’s steady,” Vancil said. “Consistent. That’s who she’s always been.”

‘I’ve seen this before’

When Sato speaks about the present day, she is deliberate.

“Losing humanity,” she said. “I’ve seen this before.”

Sato’s says her experience is relevant to today’s immigration crisis. Her talk comes on the heels of months of intense immigration enforcement and protest. When asked if it is fair to compare her experience to current events, Sato said “absolutely, 100 percent.”

She is deeply concerned by what she views as the erasure of history and the treatment of vulnerable communities. Speaking in her own words, she says watching current events unfold is a heartache.

“I feel terribly,” Sato said. “Repeating history again. I have friends in fear. I know that fear.”

She frames her concern not as political rhetoric, but as lived recognition.

“There are not many people my age alive,” she said. “If there were, this might not be happening.”

Everything she does, she repeats, is “for the sake of the children.”

Her next book, she has hinted, will include what she calls a “Bill of Rights for children.”

“To be loved. To be nurtured. To feel wanted. No matter what,” she said.

A night that stayed with people

For Mary Daffin, co-owner of The Jacquelyn, listening to Sato’s story was deeply moving.

“It was humbling seeing and hearing firsthand that the plight of 120,000 American citizens was reduced to just a few paragraphs in my history books,” Daffin said, adding that she was angered it took nearly 50 years for the government to issue an apology.

Daffin said what struck her most was Sato’s resilience and her continued engagement with the world. “I was surprised by how engaged she is in current politics, her family, and that she still has a California driver’s license,” she said.

She described the evening as sobering and authentic. “It was a living American history lesson in accepting life on life’s terms, choosing to continue, and building a life still rooted in the American Dream, even when your rights were stripped from you,” Daffin said.

Still speaking, still teaching

For Sato, the work continues. Her next event is a private discussion with survivors and students at the California Museum as part of the Day of Remembrance.

At 102, she understands time is finite. That knowledge fuels urgency, not despair.

She does not ask audiences to panic. She asks them to pay attention. To remember what happens when fear goes unchallenged. To care for one another, starting with children.

“I tell this story because I lived it,” Sato said.

And because she believes it does not have to happen again.

Rob Stewart is an executive producer and host with PBS KVIE, and reports for Abridged.