The Abridged version:

- The city of Sacramento was an early adopter of its “sanctuary city” law when the city’s ordinance passed in 1985.

- The original was designed to provide protection to refugees from the civil wars in Guatemala and El Salvador.

- Today, local leaders are calling for an expansion of the law in reaction to an uptick in federal immigration enforcement.

A nun, a retired army colonel, a humanitarian lawyer and a UC Davis professor lined up at Sacramento City Hall on a December evening nearly 40 years ago.

The group was among 13 residents who delivered public comment on a proposal to add local protections for political refugees from El Salvador and Guatemala. The policy in question would bar city employees from disseminating information about the citizenship status of its residents, and from pursuing investigations into city residents’ citizenship status.

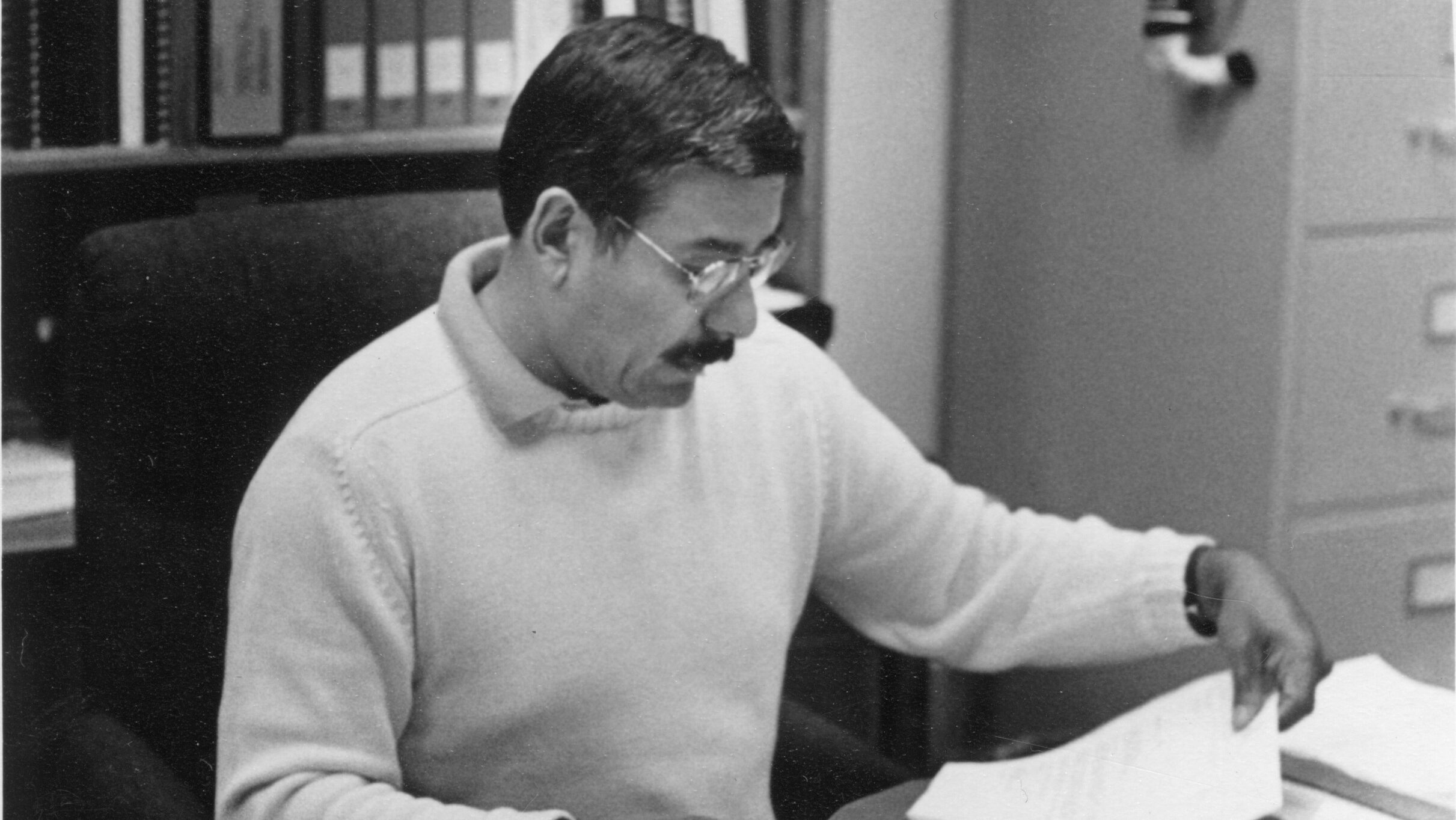

A first-term member of the Sacramento City Council, Joe Serna, championed the proposal and went a step further, requesting that the city attorney come back every six months with a report on local federal immigration activities.

The council voted 5-2 in favor of the asylum policy, cementing a resolution that stated:

“BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED, that the City of Sacramento be declared a sanctuary city and serve as a haven for refugees now residing in the City of Sacramento until they can safely return to their homeland, or until they receive federally recognized residency status …”

The ordinance is now better known as Sacramento’s sanctuary city law.

Dec. 17 marks the 40th anniversary of the sanctuary city policy. Local leaders now commend the law for providing psychological safety for the city’s immigrant communities. Recent proposals in the works would expand the law.

Civil wars in Central America propelled initial ordinance

The 1980s saw deadly civil wars in Guatemala and El Salvador that brought large numbers of refugees to the United States to seek safety.

At the same time, federal immigration efforts deported some 4,800 refugees to El Salvador in 1982 and 1983, including 50 people who were later killed in political violence, according to Sacramento’s 1985 sanctuary city declaration.

Sacramento was an early adopter of sanctuary city policies, predating San Francisco’s ordinance by four years. Berkeley was the first city in the nation to declare itself a sanctuary city in 1971.

Serna’s interest flowed from farmworker experience

Serna’s interest in the sanctuary city law “stemmed from his personal experience as a migrant farmworker in his youth,” said his son Phil Serna, who now sits on the Sacramento County Board of Supervisors.

While working in the fields, the elder Serna worked “shoulder to shoulder” with people who experienced prejudice and persecution around their immigration status, Phil Serna said.

He said his father wanted “to make sure that a long-ignored, long-disenfranchised population understood that the city of Sacramento was a place that they understood was going to be a place of welcoming, a place of refuge.”

Serna said that his father’s efforts to create a haven for asylum seekers have continued to have influence to this day.

“If nothing else, I think it has a real, tangible psychological effect,” Serna said.

Sanctuary city concepts have evolved

Over time, the concepts around sanctuary cities have grown from a response to the civil wars in Central America to a broader response to migrants in general, said Kevin Johnson, an immigration law professor and former dean of the UC Davis School of Law.

“I think now ‘sanctuary cities’ and ‘sanctuary states’ really is a political statement in important ways — that we support you and want you to know we’re here for you,” Johnson said.

Johnson added that the policies have also had a big impact on the willingness of immigrants to work with law enforcement. The policies bar local police from asking about residents’ immigration status.

“There’s a community benefit to the sanctuary policies,” Johnson said.

Sacramento threatened with federal funding cuts

The Trump administration has made multiple attempts to cut funding to cities and states that identify as sanctuaries and restrict cooperation with federal immigration officers.

Earlier this year, the city of Sacramento estimated about $175 million in federal funding was at risk due to the policy. The initial effort to rescind federal funding was blocked by a federal judge in April.

Sacramento is one of more than 50 local governments suing the federal government over the attempts to pull back federal funding. The city joined the lawsuit as one of the initial 15 jurisdictions to sue the Trump administration in March.

“For 40 years, our city has been a safe haven for refugees fleeing hardship and persecution,” said Mayor Kevin McCarty, in a statement when the city joined the lawsuit. “It is the moral tradition of our nation and our city to protect immigrants and refugees. Sacramento will uphold this legacy.”

In general, the Trump administration argues that sanctuary policies undermine public safety by preventing enforcement. Sanctuary supporters counter that local police cooperation with federal immigration authorities creates fear and distrust among immigrants.

The case is currently before the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

Local leaders want to expand sanctuary city law

Last month, a group of 16 organizations called on the Sacramento City Council to strengthen its sanctuary city policy to include broader bans on cooperation with federal immigration authorities.

Councilmembers Mai Vang, Karina Talamantes and Eric Guerra are working on an update to the ordinance, according to Vang.

“Our communities and our residents should not have to live in fear every time they go to school, go to work or attend an immigration hearing,” Vang said.

Earlier this month, nonprofits sounded the alarm over an increase in arrests of Afghan residents, including Afghan asylum seekers who attended seemingly routine hearings at a federal building in downtown Sacramento.

The sanctuary city updated policy could see changes like banning immigration enforcement officers from using city parking lots, vacant lots and garages. It also could declare support for a California law that bans Immigration and Customs Enforcement officers from using face coverings to hide their identities beginning Jan. 1.

Vang said that she’s in discussions with the interim city manager and Mayor Kevin McCarty on the sanctuary city law update, but that a formal proposal has not been submitted. The mayor could take up the matter in January, she said.

Felicia Alvarez is a reporter at Abridged covering accountability. She’s called Sacramento home since 2015 and has reported on government, health care and breaking news topics for both local and national news outlets.