The Abridged version:

- Charles Goldman moved to California from Michigan in 1958 to teach at UC Davis. His first glimpse of Lake Tahoe changed the trajectory of his life — and the future of the lake.

- Goldman is widely considered the scientific force behind the movement known as “Keep Tahoe Blue.” He created the UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center and was instrumental in the passage of state and federal laws to protect the lake.

- His work, and that of the League to Save Lake Tahoe, helped set limits on development.

- “Keep Tahoe Blue” became a shared goal across economic and political divides.

Charles Goldman was a young, newly hired instructor on his way to UC Davis from Michigan in the fall of 1958 when he took his wife and two children in their Chevy station wagon on a detour along the shore of Lake Tahoe.

That leisurely family drive helped change the course of Tahoe’s history.

What Goldman saw stunned him: a huge, deep and clear alpine lake unlike anything back home. But he also saw hundreds of homes crowding the shore and the hillsides above it. When he reached Davis, he learned of plans to add enough houses for a city the size of San Francisco.

Goldman was a limnologist — a lake scientist — and he knew the risks this growth would bring.

“I was just blown away by the beauty of that lake,” Goldman said in a recent interview. “And having come from the Midwest and observed what we call eutrophication, the greening of lakes, I recognized that Tahoe was really in danger.”

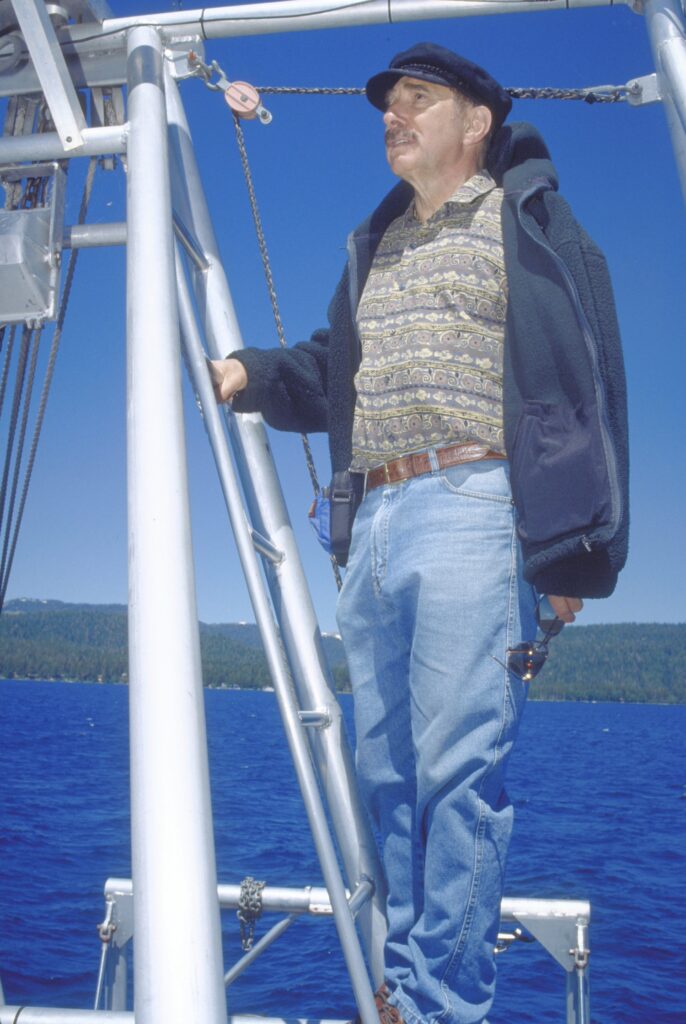

Almost immediately, Goldman began studying the lake and assessing the risks to its world-famous clarity. He never stopped. That research became his life’s work. And 67 years later, Goldman, now 94, is widely considered the scientific force behind the movement known as “Keep Tahoe Blue.”

Tracking Lake Tahoe’s clarity

He created the UC Davis Tahoe Environmental Research Center and was instrumental in the passage of state and federal laws to protect the lake. He won the prestigious Albert Einstein Award for his work. But perhaps the most important thing he did was also the simplest: He tracked the clarity of Tahoe’s water.

He began in a boat, lowering a white disk the size of a dinner plate into the water until it disappeared, then retrieved it and measured the length of the rope to which it was attached. These measurements, done regularly and eventually at dozens of locations around the lake, documented Tahoe’s clarity as it declined from about 100 feet in 1958 to 64 feet 40 years later. That metric gave residents and policymakers an easy way to understand what was at stake.

Darcie Goodman Collins, a South Lake Tahoe native, is the CEO of the League to Save Lake Tahoe, which coined “Keep Tahoe Blue” and made Goldman’s science the centerpiece of its advocacy. Goldman, she said, was the perfect partner because of his rare ability to explain science to laypeople.

“What makes him so effective is that he is an experienced and renowned limnologist, but he’s also very convincing and compelling through his visuals, his storytelling and his charisma,” she said.

Science helped change California and Nevada laws

Until the 1960s, the Tahoe Basin collected its sewage in septic tanks. Goldman warned that nitrogen from that sewage was seeping into the lake, degrading water quality and causing algal blooms that were unsightly and a danger to fish.

Tahoe officials recognized the threat and proposed treating the effluent with advanced wastewater systems and then dumping it into the lake. This seemed to many a reasonable solution. But not to Goldman, who warned that the system would not trap ammonia, a major source of nitrogen. It would have been like pouring concentrated fertilizer into the lake.

“A simple experiment demonstrated that within three days you could turn Tahoe’s crystal-clear water bright green,” he said.

Goldman’s science helped persuade the California Legislature to pass a bill requiring Tahoe to pipe its wastewater out of the basin. Nevada’s governor did the same through an executive order.

But other threats remained. Although plans to build a megacity with a freeway ringing the lake were shelved, Tahoe’s year-round population continued to grow, from about 3,000 people in 1956 to 48,000 by 1980. That brought erosion and traffic, which sent sediment and more nitrogen — from vehicle exhaust — into the lake.

Limits for development around Lake Tahoe

Goldman and the League argued for limits on development. Builders pushed back. But as the lake’s clarity declined, a new consensus emerged. “Keep Tahoe Blue” became a shared goal across economic and political divides.

“People came to the conclusion that if Tahoe lost its water quality, it would be a very bad thing for real estate and for the tourism industry,” Goldman said. “Development interests were gradually converted to recognizing the value of Tahoe’s blue water.”

That recognition led to the creation of the Tahoe Regional Planning Agency, a two-state entity sharing responsibility between California and Nevada for ensuring that development does not further degrade the lake.

It hasn’t been a perfect solution, and some now fear the agency is allowing too much development. Climate change poses new risks. But Tahoe’s clarity stabilized for many years. Had Goldman not come along when he did, the lake would be a very different place today.

“If it had taken another decade, we would have had irreversible loss in clarity,” Goodman Collins said. “With the amount of nutrients going into the lake, it would have taken forever to get it back to its natural state.”

Daniel Weintraub is a regular contributor, writing Tahoe Loco for Abridged.